Mark Taylor calls Arden “perhaps this country’s best-documented Arts and Crafts experiment, and certainly one of its most important.” But just what is the Arts and Crafts movement? In July 1904, Arden architect and planner William Lightfood Price published an essay in The Artsman appropriately titled “What is the Arts and Crafts Movement All About?” In this manifesto, he writes of that “the real motive of art…is simply to make us worth while, to make us fit to love and be loved, fit to live together.” However, modern society, with its technological innovations and industrialization, had moved away from this central core of humanity. The amassing of material goods had failed to produce the kind of satisfaction inherent in the creative arts, and he foretold of a future “where the majority of us do nothing but push buttons,” leaving workers and community members feeling unfulfilled and disconnected. Through the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Price proposed an alternative: “the opportunity to pursue happiness carries with it the opportunity to work in the kind of work that produces happiness….We must get our development and our growth…through…labor itself if we are ever again to enjoy any leadership in the world’s history.”

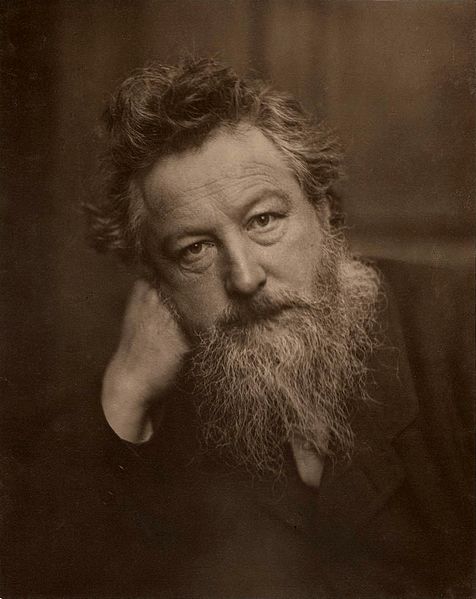

The roots of the Arts and Crafts Movement lie in England, with founder William Morris, an artist, designer, and social advocate, who remains an inspiration today.

In Pioneers of Modern Design, Nikolaus Pevsner writes that Morris and other Arts and Crafts reformers “sought to stem the tide of Victorian mass production, which its adherents believed degraded the worker and results in ‘shoddy wares.’” Rather than prescribing a distinct architectural style, the Movement stressed a re-investment in workmanship and the dignity of the worker, in order to produce better, more pleasing and practical products and cohesive, equitable communities. The medieval period, with its reverence for the artisan, was particularly inspirational to Arts and Crafts practitioners. Evidence of Morris’s place in the hearts and minds of Ardenites can be found in the Red House, named after Morris’s home in Kent, which, according to Charles Harvey and Jon Press, began his decorative arts career.

Morris influenced many artists, architects, and social reformers at home and abroad, including the American Gustav Stickley.

Although Morris was well known in his own right, Stickley was an important figure in translating Morris’s ideas for American audiences, especially Will Price. He published the aforementioned periodical The Artsman, so named after the concept of combining the artist and craftsman in the same person. Stickley promoted simple building designs and materials, which would then improve residents’ physical and moral health. Among Stickley’s ideas for the ideal Arts and Crafts home, as interpreted by Will Price, were open floor plans with few walls and furniture, as well as built-in storage and amenities, like cupboards, bookshelves, and window seats, all components of Arden homes. Arts and Crafts ideals articulated themselves particularly in Joseph Fels’ stipulations for building new homes, under Price’s direction. In April 1909, Arden Club Talk wrote that: “the one stipulation was that they should be permanent and artistic in character with stone foundations and cellars, hollow brick and concrete walls and above all, literally, the red tiled roofs so beautiful in the scenery of England and the Netherlands.”

Central to an understanding of the Arts and Crafts movement is that social ideals are reflected in the architecture, furniture, and other physical components of residents’ everyday lives, and this is certainly true of Arden. The Arts and Crafts Movement incorporates a number of intertwining themes, including the value of simplicity, the promoting of social relationships, a reverence for the centrality of nature, and the embrace of whimsy and fantasy.